a vista de pájaro quechol

2018/09/30

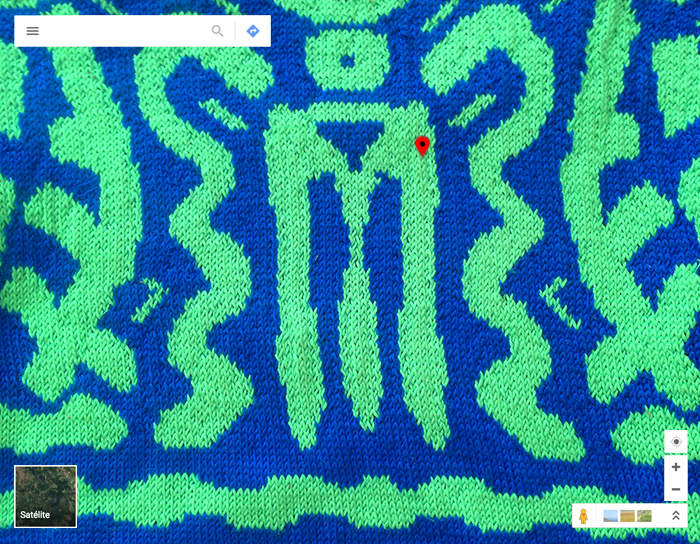

Mientras estudiaba arquitectura, mi madre dedicaba un rato cada noche a la construcción con fibra y metal de una colección maravilla de jerseys ochenteros, una suerte de edificación fantasía para el torso. En una de sus revistas alemanas de labores en punto, leo: «JACQUARDS COSMICOS. Cuando sobre él se pone el sol, salen las estrellas». Si cada uno de sus jerseys es un Universo, en My book of time aparecen por lo menos tres; vistiendo a humanos en movimiento, estáticos sobre espantapájaros o en expansión programada.

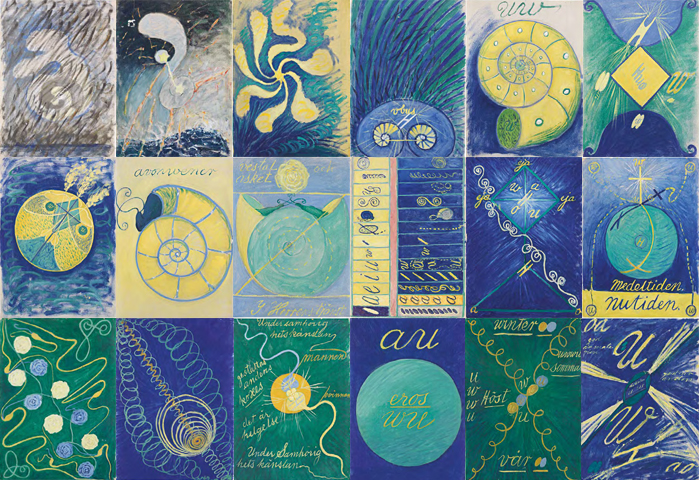

Mi abuela Gunilla me contó que de joven había conocido a un marine llamado Erik, muy estresado tras recibir la asombrosa herencia de su tía que incluía más de un millar de cuadros y unas 26.000 páginas con anotaciones; se almacenaban en su estudio de Estocolmo, donde el casero amenazaba con la quema. En ese momento no le dieron valor, o el suficiente como para sacar de allí todas sus obras en cajas de madera —el testamento decía que no debían exponerse hasta 20 años después de su muerte— y así conservar el legado artístico de la pionera de la pintura abstracta, Hilma af Klint. Una artista que a finales del siglo XIX practicaba sesiones de espiritismo y experimentaba con el dibujo automático, anticipándose a los surrealistas por unas décadas, y que en 1906 comenzó a pintar la serie de cuadros abstractos (Primordial Chaos) anterior a las consideradas primeras obras pictóricas no figurativas de Kandinsky.

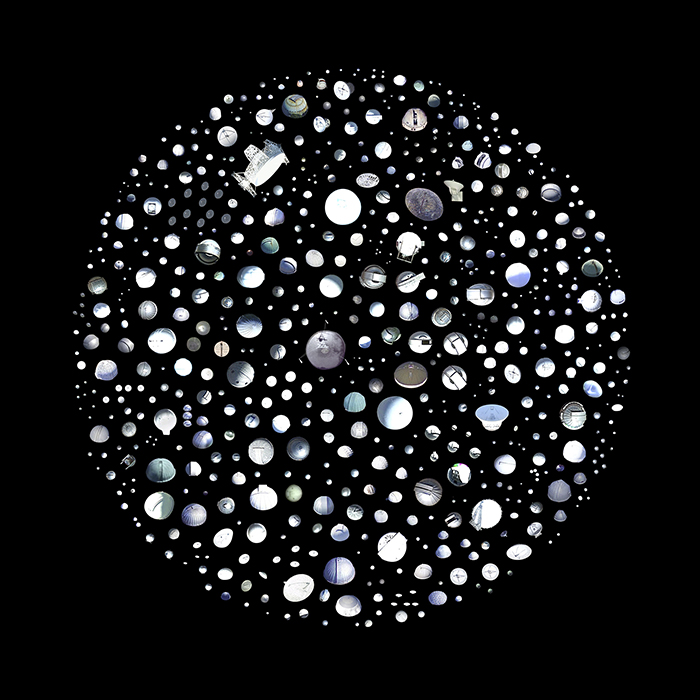

El astronauta Eugene Cernan, al ver la Tierra desde el espacio por primera vez, explicó cómo se ve nuestro planeta de polo a polo, a través de océanos y continentes, girando sin hilos que lo sostengan en una negrura más allá de la percepción. En los escritos de Jenny Odell (The Satellite Collections, 2013) se menciona que estos hilos ausentes habrían sido algo «complicado de ver» desde otro ángulo que no fuera el del astronauta, como pocas veces tomamos conciencia plena de la importancia de la vida hasta el momento previo a la muerte. Odell colecciona cosas que recorta de Google Satellite View, como 681 observatorios y telescopios: «La visión desde un satélite no es humana, pero es precisamente desde este inhumano punto de vista que somos capaces de leer nuestra propia humanidad, en todas las diminutas y repetitivas marcas que están sobre la faz de la tierra. Desde esta perspectiva, las líneas que forman las canchas de baloncesto y los dispersos rectángulos azules de las piscinas se convierten en jeroglíficos que dicen: aquí hubo gente.»

¶

a quechol bird's eye view. ≋ While studying architecture, every night my mother spent some time building a wonderful collection of 80's style sweaters with fibre and metal, a sort of fantasy construction for the torso. In one of her german needlework magazines, I read: «COSMIC JACQUARDS. When the sun sets on it, the stars come out». If each one of her sweaters is a Universe, at least three of them will appear in My book of time; while dressing humans in motion, static over scarecrows or in a programmed expansion. ≋ Once, my grandma Gunilla told me that she met a marine named Erik when she was young. He was very stressed out after receiving the astonishing inheritance of his aunt, that included more than a thousand paintings and 26,000 pages of notes stored at her Stockholm studio, with a landlord threatening to burn it down. At that time they did not value it, or just enough to take away all of this works in wooden boxes –the will said that they should be kept out from the public eye for 20 years after her death– in order to preserve the artistic legacy of the pioneer of abstract painting, Hilma af Klint. An artist who, at the end of the 19th century began holding séances, developing a form of automatic drawing that predated the surrealists for decades, and in 1906 began painting a series of abstract works (Primordial Chaos) before those considered to be the first Kandinsky's non-figurative paintings. ≋ Eugene Cernan, an astronaut on the Apollo 17, on seeing the Earth from space for the first time described how our planet looks like from pole to pole, across oceans and continents, spinning with no strings holding it up in an blackness beyond conception. In the writings of Jenny Odell (The Satellite Collections, 2013) it is mentioned that this lack of strings would have been «difficult to see» from any other perspective than the astronaut, the same way people are often unable to grasp the full weight of their lives until just before dying. Odell collects things that she cuts out from Google Satellite View, as 681 observatory domes and telescopes: «The view from a satellite is not a human one, but it is precisely from this inhuman point of view that we are able to read our own humanity, in all of its tiny, repetitive marks upon the face of the Earth. From this view, the lines that make up basketball courts and the scattered blue rectangles of swimming pools become like hieroglyphs that say: people were here.»

♯mybookoftime ♯mum ♯farmor ♯afklint ♯cernan ♯odell ♯jerseysochenteros